Written and directed by David Vail, set over one night, a young woman (Zara Flynn) spirals through drug-fuelled distraction, destructive release, and quiet moments of reflection.

Starting things out with typical club music was a clever choice by David Vail because it opens up a lot of possibilities. It doesn’t allow viewers to immediately nail down the tone or intention, and can be connected to a range of emotions and trauma, as it’s been used in such a variety of different ways in the history of cinema. However, that gets narrowed down as we’re introduced to Zara Flynn’s character, which is another strong choice as it’s with an obscured angle, pushing you to interpret the atmosphere. It quickly adds a compelling note and begins Daylight Saving Time down a complicated path.

Another key element of Daylight Saving Time which is highlighted in that very early scene is the use of sound (with sound design by Luke Savid-Harris). It’s thoughtfully layered and purposefully designed to reflect the emotional state of the character. Another great choice was keeping Daylight Saving Time purely focused on that singular character, not introducing anyone else past or present. It really cements the intimacy of the film, and lets the attention stay where it belongs to really envelop itself in the character’s journey.

The way that the timeline is structured enhances that further, allowing you to see a broader view of the character, all within under fifteen minutes. That pairs perfectly with what Vail is trying to achieve with the writing, exploring the different personas that arise in times of grief and trauma. The public one that’s outwardly compensating for that pain, with drugs and alcohol, and the underneath which is crumbling. It’s a nicely considered example of how losing someone close to you, particularly by suicide, can cause you to question everything in your life.

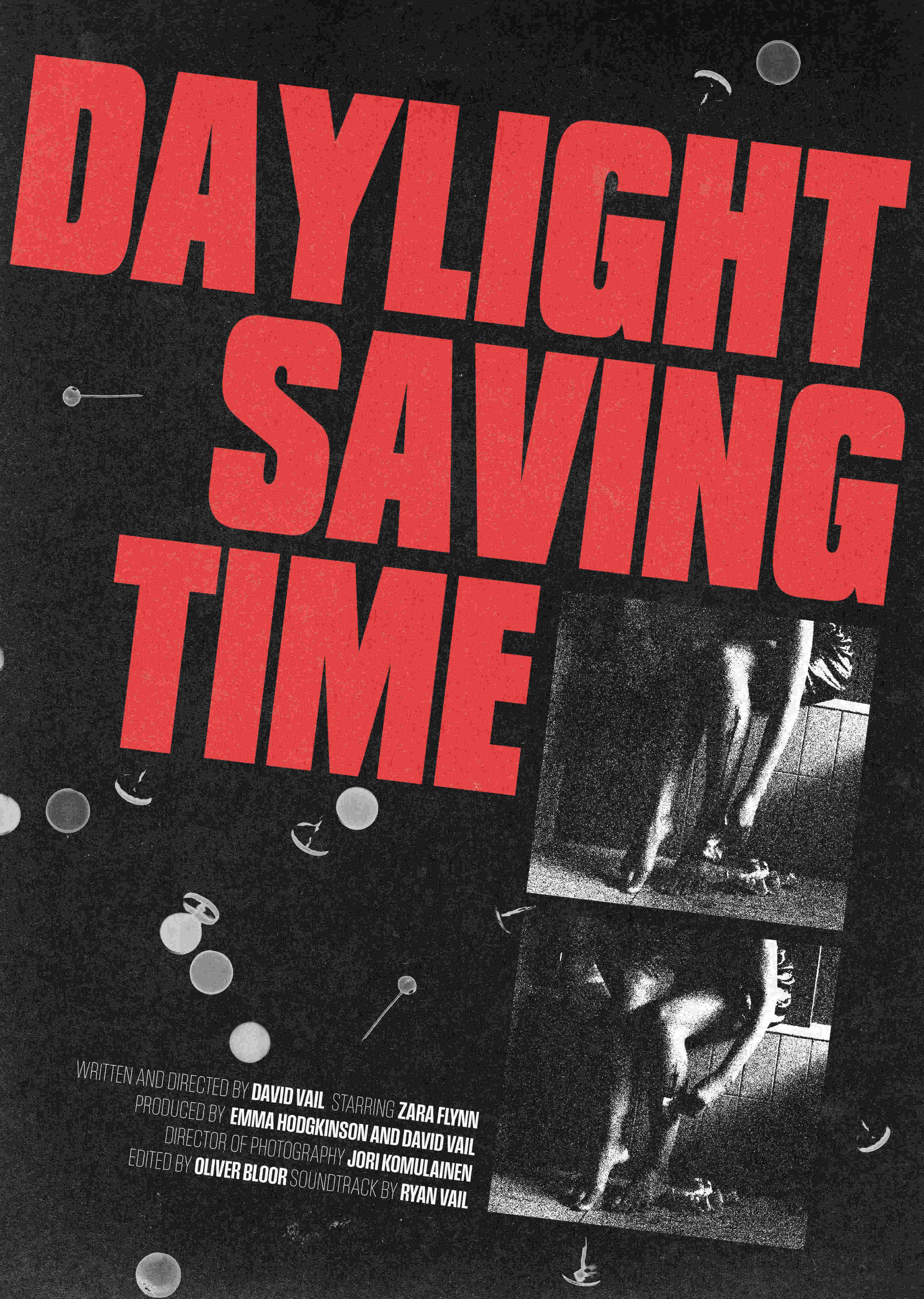

There’s a truly contemplative tone to go along with that, particularly helped by the cinematography by Jori Komulainen. It holds a superb grain to it, which creates a nicely effective contrast to Daylight Saving Time’s modern style. There’s something to it, particularly the close ups, that feels reminiscent of Georgia Oakley’s Blue Jean, especially with the complex nature of its emotions. A big part of making that work is also the performance from Zara Flynn, delivering a natural portrayal was absolutely necessary to tap into the sincerity this film requires, and Flynn did an excellent job. There’s a great range to her performance and she definitely captures the complicated emotional foundation, the vulnerability and the devastation.

Perhaps the only instance that Daylight Saving Time weakens is in its latter moments, going for more overt metaphors and artistry which move it away from its grounded tone. The intentions are certainly there, and the scenes do make perfect sense within the film, but they don’t land in the same manner causing them to slightly disrupt its otherwise smooth flow.

With grief comes a barrage of trauma, resentment, regret, guilt, shame, to name just a few, in an overwhelming blend and both Daylight Saving Time on the whole and Zara Flynn’s performance do a terrific job of capturing that experience. It’s shot well, it has a strong atmosphere, genuine emotion and tackles a difficult topic with a lot of sincerity and thoughtfulness. It’s an impressive directorial debut from David Vail, it’s showcasing a great deal of potential, as well as the kind of excellent visual and thematic quality you can achieve on a small budget.